Deployments With Schema Migrations

The typical web application runs application processes separately from its database process. More often than not, in different servers altogether. As applications evolve, it is common for new features to require changes in the database schema that the code relies on. In Ruby on Rails, these schema changes are handled through migrations: Ruby classes that implement a DSL for specifying how to change the database from an initial state, to its target state. They also contain information on how to roll-back the migration, in case a deployment needs to be undone.

A lot of web frameworks provide similar features. In the rest of the post I will talk specifically about Ruby on Rails, the one I am most familiar with. I expect that the lessons carry over beyond it.

A New Feature

For the sake of example, let us assume we are building a blog. Our database has a posts table that holds a single post on each row. Our blog as been so successful, that our product team wants us to implement a commenting system, in which each post has many comments.

We start with our initial code (V0), and an initial database state (S0):

# V0

class Post < ActiveRecord::Base

end

# db/schema.rb - S0

create_table "posts", force: :cascade do |t|

t.text "title"

t.text "body"

t.datetime "created_at", precision: 6, null: false

t.datetime "updated_at", precision: 6, null: false

end

After our code changes, our code (V1) and schema state (S1) will have changed to:

# V1

class Post > ActiveRecord::Base

has_many :comments

end

class Comment < ActiveRecord::Base

belongs_to :post

end

# db/migrate/20200103001823_create_comments.rb

class CreateComments < ActiveRecord::Migration[6.0]

def change

create_table :comments do |t|

t.references :post, null: false, foreign_key: true

t.text :body

t.timestamps

end

end

end

# db/schema.rb - S1

create_table "posts", force: :cascade do |t|

t.text "title"

t.text "body"

t.datetime "created_at", precision: 6, null: false

t.datetime "updated_at", precision: 6, null: false

end

create_table "comments", force: :cascade do |t|

t.bigint "post_id", null: false

t.text "body"

t.datetime "created_at", precision: 6, null: false

t.datetime "updated_at", precision: 6, null: false

t.index ["post_id"], name: "index_comments_on_post_id"

end

add_foreign_key "comments", "posts"

The db/schema.rb examples are provided for reference as a stand-in for the database structure. They are typically not be used in production, as the database will be evolved by running rails db:migrate which will run any pending migrations in order.

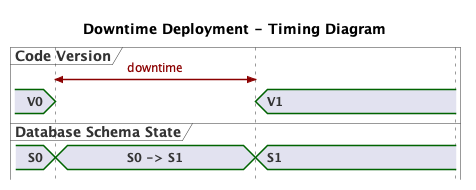

Downtime Deployment

Conceptually, the simplest deployment is one were our web app incurs some downtime. In this scenario, the sequence of operations is as follows:

- Redirect all traffic to a maintenance page.

- Stop our processes running

V0 - Install the new version of the code

V1 - Run database migrations

- Boot

V1processes - Restore traffic to the web application.

In Figure 1, S0 -> S1 represents the migration that changes the state of the database from S0 to S1. It runs during the downtime. Note that V0 always runs with schema S0, and V1 always runs with S1.

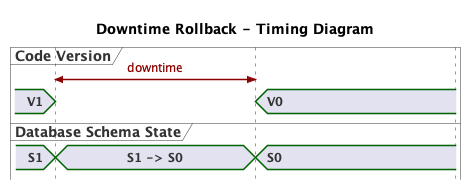

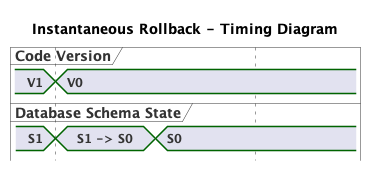

Rollback

In case we need to rollback the deployment, we would do so by doing the inverse deployment. The migration would run in a “down” migration durning the downtime:

Note that since the code for the migration – the instructions to convert S0 to S1 and vice-versa – exists only in the S1 code. This needs to be taken into account when swapping code during the deployment process.

Deploying and rolling back with downtime is straightforward, but not always desirable. Businesses usually aim to minimize downtime. The current trend in continuous deployments is to deploy small increments of code multiple times a day. Taking downtime on each deployment is unacceptable.

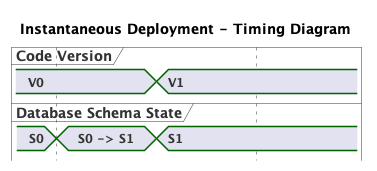

The Simplest No-Downtime Deployment

As a thought exercise, let’s imagine an instantaneous deployment: At a given moment in time our server is running V0. An instance later, the code swapped and the server is running V1.

In this scenario, when do we run our migration? Before or after the code is swapped?

Since we have been writing tests all along to develop our features, we are confident that V0 is compatible with S0, and V1 is compatible with S1. The other possible configuration are V1-S0 and V0-S1. Are they viable?

Our V1 code relies on the comments table existing in the database (S1). If the code boots and the table is missing, we will get exceptions similar to:

post.comments

# => ActiveRecord::StatementInvalid (PG::UndefinedTable: ERROR: relation "comments" does not exist)

The Rails tooling makes it hard to test this configuration. For example, in development requests will not execute if there pending migrations, with an error message being shown directing you to run them. The underlying assumption is that your code will not work without running the migrations. We can observe that is the case in our example and conclude that V1-S0 is not a viable configuration.

What about V0-S1? As defined, S1 is purely additive – meaning new things are added, nothing removed. The implication is that V0 code is compatible with S0 and S1. We can test this combination by creating a branch that has the V0 code, and the S1 migrations, but does not include any of the V1 changes. If all the tests pass against this configuration, it gives us confidence that this is a compatible state. This branch does not need to be deployed, it serves only as a canary.

We can tabulate the above in a compatibility matrix:

S0 |

S1 |

|

|---|---|---|

V0 |

✓ | ✓ |

V1 |

𐄂 | ✓ |

We can deduce that during our deployment, the migrations need to run before the code-swap phase, to prevent the only incompatible configuration (i.e. V1-S0).

In case that a rollback is needed we would be in a position in which V1 is running on an S1 schema. It continues to be true that V1 is only compatible with S1. The implication is that the migration rollback needs to occur after the code-swap. If at all. Depending on what went wrong, sometimes a code swap without the database migration is enough to address issues.

We’ve determined on which side of the code swap our migration needs to run. S0 -> S1 is shown as taking a certain amount of time. During this period, we can’t be sure in which state (S0 or S1) our database is in, but we know that V0 is compatible either way. Do we have to worry about what state in-between S0 and S1? It depends. The Rails documentation states:

On databases that support transactions with statements that change the schema, migrations are wrapped in a transaction. If the database does not support this then when a migration fails the parts of it that succeeded will not be rolled back. You will have to rollback the changes that were made by hand.

If you are using Postgres, transaction support ensures that you are in either S0 or S1, as long as you are making changes in a single migration. For other databases, like MySQL, this is not the case. In our example, the migration produces one – and only one – data definition statement (CREATE TABLE...). It will either succeed or fail. Even if transactions are not supported, we probably don’t need to worry. For the purpose of the rest of the post, I will assume then that we can be sure that our database is either in S0 or S1, and that SO -> S1 implies that we could be in either state.

Short-Downtime Deployment

Heroku is a managed hosting service popular with Rubyists for good reason. It abstracts away a lot of the complexity of setting up an opinionated deployment pipeline. In a typical Rails app deployed to Heroku, a Procfile is checked in to the project, specifying the applications processes:

web: bundle exec puma -p $PORT -e $RAILS_ENV

sidekiq: bundle exec sidekiq

Every time git’s master branch is pushed to Heroku’s remote server, the code will be packaged, existing processes (in this case web and sidekiq) will be gracefully terminated, and subsequently restarted using the new code package. Without any other configuration, no migrations will be run. The developer is left to run them manually either before or after the deployment.

A more robust and automated deployment would take advantage of Heroku’s Release Phase. This is a special type of process that runs on each deployment and can be specified in the Procfile as follows:

release: bundle exec rake db:migrate

web: bundle exec puma -p $PORT -e $RAILS_ENV

sidekiq: bundle exec sidekiq

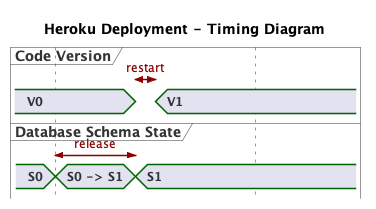

With a release process definition in place, Heroku will execute it after packaging V1, but before stopping the existing processes (V0) and restarting with the new code (V1).

In our code example, we identified that the migration needs to run on the V0 side of the deployment, which matches the “Heroku way”. The diagram shows a brief interval in which neither V0 or V1 is running. This is the pause between the shutdown of old processes and starting of new ones. A partial log (edited for clarity) shows this pause:

Heroku deployment log:

2020-01-06T23:48:28.253359+00:00 app[api]: Deploy 6909d7c6 by user ylan@...

2020-01-06T23:48:28.660547+00:00 app[api]: bundle exec rake db:migrate

2020-01-06T23:48:28.253359+00:00 app[api]: Running release v99 commands by user ylan@

2020-01-06T23:48:33.579124+00:00 heroku[release.9811]: Starting process with command `/bin/sh -c ... '"'"'bundle exec rake db:migrate'"'"' else bundle exec rake db:migrate fi'`

2020-01-06T23:48:34.225131+00:00 heroku[release.9811]: State changed from starting to up

2020-01-06T23:48:36.000000+00:00 app[api]: Build succeeded

2020-01-06T23:48:40.262074+00:00 app[release.9811]: (1.5ms) SELECT pg_try_advisory_lock(5844823552245979560)

2020-01-06T23:48:40.280848+00:00 app[release.9811]: (2.3ms) SELECT "schema_migrations"."version" FROM "schema_migrations" ORDER BY "schema_migrations"."version" ASC

2020-01-06T23:48:40.298219+00:00 app[release.9811]: ActiveRecord::InternalMetadata Load (1.7ms) SELECT "ar_internal_metadata".* FROM "ar_internal_metadata" WHERE "ar_internal_metadata"."key" = $1 LIMIT $2 [["key", "environment"], ["LIMIT", 1]]

2020-01-06T23:48:40.314867+00:00 app[release.9811]: (1.6ms) SELECT pg_advisory_unlock(5844823552245979560)

2020-01-06T23:48:40.419733+00:00 heroku[release.9811]: State changed from up to complete

2020-01-06T23:48:40.410205+00:00 heroku[release.9811]: Process exited with status 0

2020-01-06T23:48:41.931703+00:00 app[api]: Release v99 created by user ylan@

2020-01-06T23:48:42.257846+00:00 heroku[web.1]: Restarting

2020-01-06T23:48:42.274533+00:00 heroku[web.1]: State changed from up to starting

2020-01-06T23:48:43.021851+00:00 heroku[web.1]: Stopping all processes with SIGTERM

2020-01-06T23:48:43.032213+00:00 app[web.1]: [4] - Gracefully shutting down workers...

2020-01-06T23:48:43.304215+00:00 heroku[web.1]: Process exited with status 143

2020-01-06T23:48:46.489798+00:00 heroku[web.1]: Starting process with command `bundle exec puma -p 48278 -e production`

2020-01-06T23:48:48.340083+00:00 app[web.1]: [4] Puma starting in cluster mode...

2020-01-06T23:48:48.340107+00:00 app[web.1]: [4] * Version 4.3.1 (ruby 2.6.5-p114), codename: Mysterious Traveller

2020-01-06T23:48:48.340109+00:00 app[web.1]: [4] * Min threads: 5, max threads: 5

2020-01-06T23:48:48.340110+00:00 app[web.1]: [4] * Environment: production

2020-01-06T23:48:48.340115+00:00 app[web.1]: [4] * Process workers: 2

2020-01-06T23:48:48.340117+00:00 app[web.1]: [4] * Preloading application

2020-01-06T23:48:51.932771+00:00 app[web.1]: [4] * Listening on tcp://0.0.0.0:48278

2020-01-06T23:48:51.932941+00:00 app[web.1]: [4] Use Ctrl-C to stop

2020-01-06T23:48:51.939376+00:00 app[web.1]: [4] - Worker 0 (pid: 6) booted, phase: 0

2020-01-06T23:48:51.941703+00:00 app[web.1]: [4] - Worker 1 (pid: 9) booted, phase: 0

2020-01-06T23:48:52.360202+00:00 heroku[web.1]: State changed from starting to up

Once the migrations are done, the web workers are sent a shut down signal. They will finish processing request already in-flight (provided it they don’t take too long). New requests will be held by the Heroku router until the new process is ready to accept connections. The relevant lines show an interval of ~10 seconds:

2020-01-06T23:48:42.274533+00:00 heroku[web.1]: State changed from up to starting

2020-01-06T23:48:52.360202+00:00 heroku[web.1]: State changed from starting to up

Is that acceptable? It depends on your application. For this particular deployment, the Rails application is as small as they come. It has but a handful of models and gems, and can boot in development mode in under 2 seconds. Typical Rails apps take significantly longer to boot, because they have larger code bases and include many more gems. It’s not uncommon for applications to take close to one minute to boot in production.

Another consideration is the amount of traffic to the app. If we field a couple of request per second and have a pause of 10 seconds, we won’t see more than a few dozens requests queued up. Our application would probably catch up in a few seconds and no request would be dropped. On the other hand, higher traffic apps with longer boot times might not be so lucky.

Effectively, we can think of Heroku deployments with release phase, as a short-downtime deployment. It provides an automated way to run migrations (albeit by restricting them to running before the code swap), it ensures that only one version of the code is running at any one time, it is relatively simple to reason about, and more importantly, it’s accessible to any developer with one line of configuration.

No Downtime Deployment

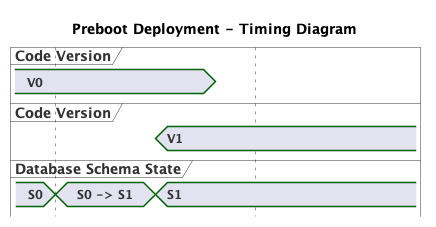

If your app needs are not yet satisfied, there are ways that we can improve on the previous method. As we saw, the app’s boot time is main driver in the delay of request handling. We can improve Rails’ boot time only so much. What if we boot the new processes before stopping the old ones? This is exactly what Heroku’s Preboot does.

Heroku Preboot – and many other deployment pipelines – work by booting the processes with V1 without stopping the V0 processes. Once all the new processes are healthy and receiving traffic, old processes are stopped. Effectively, ensuring that request are served continuously. Similar techniques can be used using container orchestration frameworks (e.g. Docker Compose, Kubernetes) or vendor-specific technologies (e.g. AWS Elastic Load Balancers, Auto-Scaling Groups, etc).

Figure 6 illustrates that we continue to enforce the constraints we identified with regards to code version and schema state. V0 runs with either schema S0 or S1, and V1 runs only with schema S1. Critically, this type of deployment introduces something new: Both V0 and V1 are going to be running – and receiving – traffic at the same time. This V0/V1 - S1 configuration will introduce several complications. Let’s see a few examples.

A user loads one of our blog post. The request gets routed to a server running V0, so they doesn’t see any comments. Other requests may be routed to a V1 server. Those request will show comments. For the duration of the V0/V1 interval this will be the case. Users might not even notice that sometimes comments are shown and sometimes they are not. In this case, this might not seem like a big deal, but consider other features introduced in a deployment, like a long awaited release of a new iPhone.

Since V1 is ready for comments, each of our blog pages now shows a form to submit a new comment. What happens if a user submits the form (“First!”) and the POST request gets routed to the /post/:id/comments endpoint on a V0 server? That endpoint doesn’t even exist. This will likely result in a 500 error from the server, and a new report to the error tracker (e.g. Bugsnag, Airbrake, etc). If we are not thinking about the possibility of two version of code running simultaneously the reports will look incoherent and we are unlikely to reproduce in a development environment.

A similar issue will happen with background workers. Let’s say that V1 introduces a new background worker CommentNotifierWorker. Its execution is scheduled on each comment creation. During deployment, a V0 might pick up that job, only to fail immediately because it can’t instantiate that class. The default Sidekiq configuration will retry jobs with an exponential back-off, which more than likely result in the job being retried later by a V1 worker, providing some resiliency. However, it is not ideal to rely on that. For some workers, retrying is not an option either (e.g. processing a credit card transaction).

The interaction between different versions of code running simultaneously can be complex and hard to reason about. Its non-deterministic nature also makes it difficult to simulate in a QA environment. A few strategies for mitigation come to mind.

Session affinity, also known as sticky sessions, can provide some relief. Systems that have session affinity route all requests from the same user (typically identified by a cookie) to the same server. Traditionally they are used for systems that keep state in memory, and would otherwise not have access to the user’s data. For the purposes of this discussion, it would help us ensure that users only saw one of the two versions, but not both. While that approach could work for web requests, it does not help with background workers. Keep in mind that session affinity has fallen out of favor because of its scaling considerations. Heavy users can overload their servers, while the rest of the system is idle. In contrast, when any request can be fielded by any server, resources are typically better utilized.

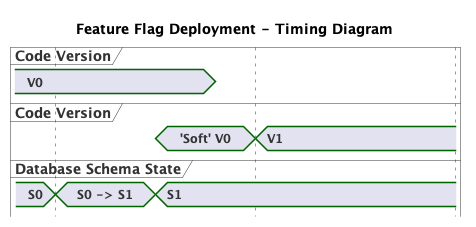

Another approach is the use of feature flags: New code paths are introduced with conditionals that depend on a run-time setting. For example, V1 view code could show the comments (and the comment form) only when a runtime flag is enabled. The flag would stay disabled until after the deployment.

Our V0/V1 interval now becomes a V0/'Soft' V0 interval. 'Soft' V0 is the mode in which V1 runs when the feature flag is disabled. We’ve made some strides in making it easier to reason about multiple versions of code running at once, at the expense of introducing more complexity in our code, and adding a whole new configuration – 'Soft' V0 - S1 – for QA to test. We’ve also now have the burden to remove the feature flag conditionals in the code in a follow-up deployment, and the effort that goes along with that.

Closing Thoughts

In this post we analyzed a simple product feature that requires a purely additive migration. We established a framework for reasoning about on which “side” of the code swap to run the migration when deploying. The discussion did not touch upon other types of migrations, like removing a table or renaming a column, left for another time.

Then we discussed how our deployment strategy has to be kept in mind while writing our code. A downtime deployment is the easiest to reason about. A Heroku-style deployment improves on that, while still maintaining simple code semantics. True no-downtime deployments cause inescapable complexity. We saw a few ways to deal with it.

Also left out of this post is a discussion about changing the schema in large databases. Those concerns will also impose further constraints. For a peek at some of those strategies see the strong_mirations gem.

Find me on:

- Bluesky at @ylan.segal.family.com

- Mastodon at @ylansegal@mastodon.sdf.org

- By email at

ylan@{this top domain}